Why it’s time to start thinking about batteries for your rooftop solar

By Dan Lander

TECHNOLOGY AND ENGINEERING Research by UniSA PhD candidate Vanika Sharma has found that batteries which store energy from rooftop solar are now able to pay for themselves within the warranty period. Image: A commercial-scale TeslaPowerpack battery system.

TECHNOLOGY AND ENGINEERING Research by UniSA PhD candidate Vanika Sharma has found that batteries which store energy from rooftop solar are now able to pay for themselves within the warranty period. Image: A commercial-scale TeslaPowerpack battery system.With the boom in rooftop solar in recent years, a growing number of consumers are considering battery storage options in order to become less dependent on the main power grid.

Many consumers have been waiting for the market to cross the point at which a battery will save them enough money to “pay itself off” within its warranty period, and researchers at UniSA believe that point may have arrived for South Australian residents – under certain conditions.

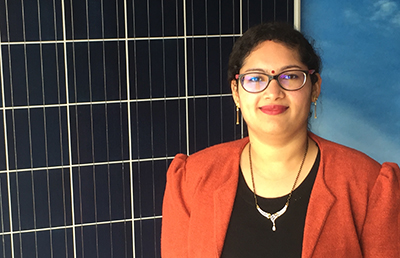

PhD candidate Vanika Sharma.

PhD candidate Vanika Sharma.PhD candidate Vanika Sharma, from UniSA’s School of Engineering, recently published a paper in the journal Renewable Energy that shows an optimally sized battery can now be economically beneficial in South Australia because of the combination of government subsidies, abundant sunlight, high electricity costs and relatively low feed-in tariffs.

“The crucial thing is to ensure you are getting the right size battery, and getting it at the right price,” Sharma says. “But if you are, then you can now have a battery that will pay itself off in the warranty period, which is the main concern for most people.”

The Advertiser, 25 June 2019.

The Advertiser, 25 June 2019.While Sharma warns there are still many cases where batteries are not yet cost-effective, she has developed a calculation method to determine whether an optimally sized battery will pay itself off based on a range of factors, allowing consumers to adjust their initial investment against projected savings.

“The optimal battery size depends on various factors, such as load and PV (photovoltaic) generation patterns, battery cost and characteristics, retail price and feed-in-tariff of grid electricity,” Sharma says. “But this method can assess all this efficiently, and that allows people to make the right choice for their circumstances.

“Right now, in South Australia, the break-even cost for installing battery using this method is around $400 per kilowatt hour of battery capacity, and with the current subsidies of $500 per kilowatt hour, and retail prices on some batteries lower than $900 per kilowatt hour, you can have a cost-effective system.”

Sharma and her co-researchers, Dr Mohammed Haque and Professor Mahfuz Aziz, are also investigating whether storage alternatives, such as shared ‘community’ batteries, may present further benefits in both cost and system efficiency.

“The focus of the research is to minimise the waste of PV, and so we’re also looking at whether it is more effective to have batteries on every home, or a central battery that could accommodate more PV, which would then also save distribution costs for providers,” Sharma says.

Dr Haque says that residential battery energy storage systems not only provide financial benefits to customers but address some of the operational issues associated with power generation, transmission and distribution.

Prof Aziz says the use of battery energy storage systems is likely to proliferate in the years to come.

“Future research and development should focus on how to leverage such storage to improve power system operation,” Prof Aziz says.

Other Stories

- Using free public wifi could be putting you at risk of cyber attack

- Why it’s time to start thinking about batteries for your rooftop solar

- Storytelling technology to revolutionise criminal convictions

- Being environmentally responsible is good for the bottom line

- From the Vice Chancellor

- Achievements and Announcements

- Problematic sexual behaviour among young children raises concerns for teachers

- UniSA thriving in World Young University rankings

- Mobiles can help you better manage your medications

- Hoodie culture a winner for Aboriginal artist

- War veterans tap into their creative side at UniSA

- We asked a UniSA student to review MOD.’s new exhibition

- What it’s like for a student from Peru to study in Adelaide

- The latest books from UniSA researchers

- Maple Leaf, microengineering school and Refugee Week events