25 June 2021

AUTHOR: ANNABEL MANSFIELD

Since the first Adelaide Festival in 1960, South Australia has firmly set its sights on building a flourishing and successful festivals and events sector.

In 2020, COVID-19 decimated arts everywhere, and more than 12 months later, the sector is still recovering. Here, we reflect on South Australia’s past glories and consider what’s needed to secure a strong future for the industry.

Looking back, it’s hard to imagine how some of South Australia’s primetime events ever got the tick of approval. From the jetty-jumping hijinks of the Birdman Rally, to the precarious creations of the Milk Carton Regatta, events in the 1970s and 1980s were far freer than any we could imagine today.

Fast forward to the present day and things are very different. Putting aside the obvious impacts of COVID-19 for a moment, the past 30 years have seen South Australian events move away from risky crowd-pleasers, to a professional and expanding calendar of offerings that not only showcases the very of best of South Australia, but that also embraces its moniker as the Festival State.

The journey has been colourful. Over the years, the state has delivered the world-renowned Festival of Arts, an electrifying F1 Grand Prix (and its later ‘evolution’, the V8 Supercars), and the world’s second largest annual arts festival, the Adelaide Fringe. South Australians have welcomed world music, art and dance through WOMADelaide, literary insight in Adelaide Writers’ Week, international cyclists to the Tour Down Under, and indulged in the delights of Tasting Australia.

While the list goes on, it’s fair to say that festivals and events in South Australia have not only matured, but developed into a sophisticated, contemporary and valuable sector that generates more than $392 million in tourism expenditure to the state each year.

Then, in March 2020, everything came to a stop. When the pandemic struck, the tourism and events sector was hit hard. State and international borders closed and, coupled with restrictions on public and private gatherings, most in-person festivals and events had to be cancelled, postponed or curtailed.

The economic impact was significant. Heavily reliant on domestic and international visitors, the value of tourism in South Australia fell from $8.1 billion in 2019 to $4.7 billion in 2020 – a decrease of $3.4 billion.

It’s a big economic knock, but as events and festivals slowly re-emerge, albeit in various COVID-19-safe forms, Professor Susan Luckman, Director of UniSA’s Creative People, Products and Places Research Centre, says South Australia is pioneering the way.

“You only need to look at South Australia’s recent festivals and events to see just how well we’re performing in the new ‘COVID-19 normal’, and how lucky we have been to be able to do so,” Prof Luckman says.

“Our Adelaide Film Festival was among first to allow people back into the cinema for an in-person experience; our WOMAD was the first back on stage worldwide; and our signature Adelaide Fringe Festival celebrated its 60th anniversary with more than 900 events over 31 days, attracting an estimated attendance of 2.7 million.

“Of course, it’s not been without compromise. Each unique event has undergone a stringent management plan, including capacity controls, e-ticketing, QR entry codes, COVID-19 marshals, rules on dancing, and social distancing.

“We have some key advantages in Adelaide that enable us to move more events outside. We live a city that’s blessed by mild weather, we’re surrounded by urban parklands, and we have a deeply interconnected and collaborative arts and cultural sector.

“Plus, when the pandemic hit, we were nearing the end of the 2020 March festival season, giving us a whole year to consider how to navigate COVID-19 in 2021.

“For WOMADelaide, event organisers pivoted to a series of sunset concerts in a new gated, seated, and outdoor space, which not only was at least able to maintain the music festival’s parkland heritage but also allowed people to dance (if only just in front of their ticketed chairs).

“Importantly, these tweaks – big or small – let people enjoy face-to-face performances. And, how much did we miss being physically immersed in arts and culture?”

As Australia starts to see glimpses of a past ‘normal’, UniSA’s Dr Freya Higgins-Desbiolles suggests considering whether tourism and events should return as they once were, or whether there are opportunities for change.

“The pandemic has been an inadvertent and radical wake-up call for the arts sector, not only forcing it to be more inclusive and community focused, but also reminding us to be more sustainable,” Dr Higgins-Desbiolles says.

“Around the world, overtourism is a growing problem, damaging communities and dismissing the needs of local communities. In Australia, it’s generally less of an issue, but when ‘Mad March’ rolls up, some residents are understandably irked by the congested roads, noise, and the sometimes-unruly tourists.

“For tourism, arts, and events to have a sustainable future, we need to reorient our focus and put the wellbeing and interests of local residents at the forefront.

“For example, the amount of pop-up shows across Adelaide’s suburbs and surrounds during the Fringe demonstrated a connection to local communities, invigorating the areas and delivering positive economic and social flow-on benefits.

“But events can also be a catalyst for social wellbeing. Take for example, Adelaide-based events-styling company, GOGO Events, which supports vulnerable and marginalised people into employment via events, paid work opportunities, training, qualifications and connections.

“So, arts, tourism and events can positively influence a community. It’s just about thinking outside the square and going beyond economics to ensure social and community benefits.”

Building a sustainable ecosystem for tourism and the arts is the focus of a new industry report prepared by Arts and Cultural Leadership expert, UniSA’s Professor Ruth Rentschler, who says that the future of the sector relies upon strategy and collaboration.

“In a post-COVID-19 world, arts, festivals and events need to be ‘smart’ and ‘slow’ with a greater focus on audience engagement than audience volume,” Prof Rentschler says.

“Considering this, the challenge will be to foster and develop an ecosystem that includes both face-to-face and streamed performances, as well as for the public to embrace both.

“This year’s Fringe saw many artists, musicians and institutions adopt live streaming to facilitate home-viewing, which was great as it connected a broader audience and enabled artists to generate income amid restrictions at venues.

“Similarly, the ‘Double Your Applause’ initiative let Fringe goers purchase an additional seat to compensate artists for limited audience capacities.

“When we consider that 80 per cent of Fringe shows were sourced locally, and that Fringe ticket sales exceeded targets by $1 million, it’s clear that local South Australian artists, including First Nations performers, are delivering the goods.

“We must not forsake the artist for the dollar.”

While the significant uplift in local talent is a step towards a more sustainable arts sector, more must be done, especially in terms of cooperation and coordination, says Senior Lecturer in Arts and Cultural Management, UniSA’s Dr Boram Lee.

“Building greater collaboration and synergy among arts festival organisers and government stakeholders is essential, especially when we consider the significant economic contribution of the sector to the state,” Dr Lee says.

“Post COVID-19, stakeholders will need to move beyond the operational requirements of individual festivals, to become more cohesive, cooperative and strategic.

“We will need to see more knowledge and data sharing, greater interactions across departments, as well as training initiatives to support and encourage artists and performers to build their entrepreneurial spirit.

“But beyond this – beyond the structures, the finances, and the ideas of festivals and events – we must remember what the arts really mean to us: they’re an expression of human experience, an opportunity to share views, opinions and dream, and a vital part of who we are as human beings.”

From our media centre

Frog cakes and Fruchocs: famous foods attract valuable tourist dollars

From the mouth-watering baked goods of the Port Elliot Bakery, to the ocean freshness of Coffin Bay oysters, local foods are fast becoming a major drawcard for domestic tourists, especially amid COVID-19, where the safest and most reliable travel options are within our own state.

Now, a world first study from the University of South Australia and the University of Technology Sydney, shows just how important local foods can be for domestic tourism, as the findings show how food can potentially increase visits to local areas by tenfold.

UniSA’s Dr Janine Williamson says that this is the first study to provide empirical evidence that leisure tourists – not only ‘foodies’– consider food experiences an important part of their travel experience, and that this presents extremely valuable opportunities for domestic tourism.

“With international travel on indefinite hold since the onset of COVID-19, local tourism bodies must now focus their efforts on domestic offerings if they are to recover lost tourism dollars,” Dr Williamson says.

“Since the pandemic, the monthly average loss in tourism receipts from all inbound markets is estimated at $2 billion – a drop of 52 per cent rom the previous year.

“Our study shows that tourists who consider local foods a valuable element of their holiday experience, are 10 times more likely to consume food on their next trip, as compared to those who did not think that food was important.

“This means that there is a unique opportunity for local and regional enterprises to change the tourist landscape, and to do this through food.”

The research highlights the importance of local food experiences to explore and experience the local culture.

“Tourists who are culturally motivated to consume local food, will seek out new, unique and authentic food experiences,” Dr Williamson says.

“To maximise the potential of local food, tourism bodies must be engaged with their local food operators and proactively look for ways to include them in promotional strategies.

“Whether it’s looping in the Balfour’s Frog Cake, a Barossa Shiraz, or even the regular round-the-corner line up to the Port Elliot Bakery, finding ways to include local food experiences in tourism campaigns is a sure-fire way to maximise tourism dollars.

“By building travel motivations that include food, and by promoting the social, cultural and authenticity that local foods can bring to the tourist experience, regions could significantly expand their reach, engagement, and importantly, their income.’’

Images:

Adelaide Festival of the Arts: (cropped) The Outdoor Artists, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

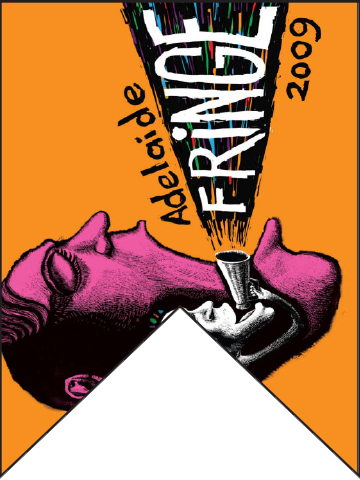

Adelaide Fringe: Flickr - Viv Smythe

Pigs Might Fly' in the Birdman Rally: adelaiderememberwhen.com.au

Milk carton regatta: adelaidenow.com.au

Milk carton regatta: Adelaide Memories Facebook

Formula One Grand Prix: Flickr - Juan Pablo Donoso

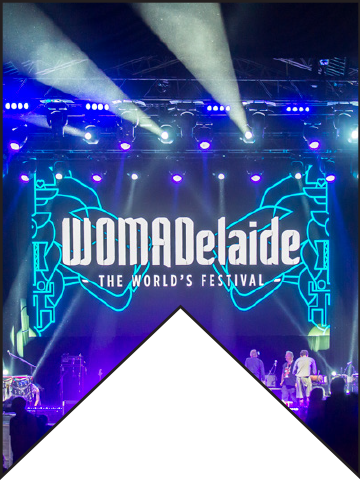

WOMADelaide: Flickr - John Kol

Tasting Australia: Flickr MBC Foods

Clipsal 500: (cropped) User:F1 power, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Adelaide Cabaret Festival: Flickr - Adelaide Festival Centre

Adelaide Festival of Arts:

1960-present

This landmark Festival of Arts is one of the world's major celebrations of the arts. Comprising many events, including WOMADelaide and Adelaide Writers’ Week, it celebrates the transformative power of the arts. In 2020, its 60th year, it attracted nearly 400,000 attendees and generated $70.2 million expenditure for the SA.

Adelaide Fringe Festival: 1960-present

As the biggest arts festival in the Southern Hemisphere, the Adelaide Fringe transforms Adelaide and greater South Australia with a month-long calendar of eclectic and vibrant events. A not-for-profit, open access festival, it brings together 6000+ independent artists in 300+ venues. It collectively presents more than 1200 shows.

Birdman Rally: 1975-1986

The first Birdman Rally in 1975 saw more than 25,000 people line the River Torrens to watch costumed contestants run, jump and attempt to ‘fly’ crazy contraptions over the water from a six-metre-high platform. In 1976, the Birdman Rally was moved to Glenelg beach, with the final event held in 1986.

Milk Carton Regatta:

1980-1987

First staged at the Patawalonga River in 1980, the Milk Carton Regatta attracted thousands of spectators to watch hundreds of milk carton creations and their crews take to the water, vying to be first vessel to cross the finishing line. The last regatta was held in 1987 after the ‘Pat’ was deemed unsafe for recreational activities.

Formula One Grand Prix:

1985-1995

Adelaide roared to life in ’85 as it hosted the first Australian F1 Grand Prix. A favourite with the drivers, who quickly proclaimed it as the best street circuit in F1 racing, it fast-tracked Adelaide to the height of popularity, with more than 200,000 spectators passing through the turnstiles by the end of the first four-day event.

WOMADelaide:

1992-present

This popular world music festival was first run biennially in opposite years to the Adelaide Festival of Arts, becoming an annual event in 2003. Attracting growing audiences of more than 95,000 it encourages people to experience music from other cultures as a way of developing global understanding.

Tasting Australia:

1997-present

A 10-day celebration of food and wine, Tasting Australia is Australia’s premier eating and drinking festival. Celebrated as one of the most exciting food festivals in the world, Tasting Australia is the nation’s longest-running food and wine festival generating expenditure of more than $5.4 million for SA.

Adelaide 500: 1999-2020

The V8 Supercars revved Adelaide to life in 1999, attracting around 300,000 motorsport fans. Deploying a shortened version of Adelaide’s Grand Prix circuit, it seemed to compensate for the F1 loss. In 2020, it was cancelled, with COVID-19, increased costs and declining public interest cited as reasons for the event's demise.

Adelaide Cabaret Festival:

2001-present

The biggest cabaret festival in the world, the Adelaide Cabaret Festival is a major event in the international and Australian arts calendar. In 2020, the Adelaide Cabaret Festival was cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but is back in 2021.

Other notable mentions:

- Adelaide Christmas Pageant (1933-present)

- Tour Down Under (1999-present)

- Adelaide Biennial of Art (1990-present)

- OzAsia Festival (2007-present)

- Adelaide Guitar Festival (2007-present)

- South Australian Living Artists (SALA) Festival SALA (1998-present)

You can republish this article for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence, provided you follow our guidelines.