Article Lead In

22 November 2021

AUTHOR: DAN LANDER

Despite growing global appetite for electric vehicles, Australia remains hesitant to commit to emissions-free motoring. What will it take to change that?

In late October 2021, a report by Morgan Stanley suggested Tesla sales for the third quarter of the year had jumped 70 per cent, at a time when global production of cars fell by almost 20 per cent. The report noted Tesla enjoyed the largest profit margins of any car manufacturer. “We expect Tesla will invest this margin into price, capability, and scale … potentially adding vice-like pressure on established auto companies. The combination is potentially disruptive for the legacy players,” the report stated.

Disruption or not, most of those legacy players have already heavily invested in electric vehicles (EVs) with many major brands – including Honda, Volvo, General Motors and Audi – announcing plans to cease production of fossil fuel vehicles well before 2030.

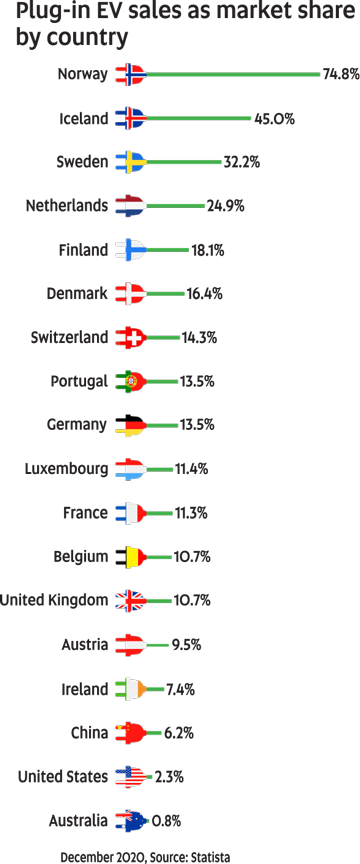

This manufacturing shift has been driven, in part, by improved battery technology and reduced costs, with some analyses suggesting EVs will be cheaper to produce than petrol vehicles by 2027. The shift has also been driven by increased consumer uptake, particularly in Europe – in Norway, more than 80 per cent of new cars sold in 2021 have been electric; in Iceland, this figure is more than 55 per cent, and in Sweden just under 40 per cent.

In Australia, by contrast, EV sales in the first half of 2021 accounted for 1.57 per cent of new vehicles – and that figure includes petrol-electric hybrids. While that may be disturbingly low, to put a positive spin on it, there were more EVs sold in Australia in the first half of 2021 than all of 2020. That, along with the Federal Government’s recent commitment to a net zero emissions target by 2050, suggests Australia might finally be ready to join the EV revolution. What will it take to shift the national car-buying market to a post-petrol perspective? Current research indicates it may require complex partnerships across a range of sectors.

The chicken and egg problem

Senior research fellow at UniSA, Dr Akshay Vij, has collaborated extensively with industry and government partners researching transport sector challenges, and says some of the hesitance in the Australian EV market is not unique to this country.

“Consumers across the world are still somewhat reluctant to adopt EVs,” Dr Vij says.

“It's a new technology, and there's always hesitation around adopting a new technology. A car is the most expensive purchase that any household makes outside of buying the house, so hesitation is greater in this area than many others.

“Globally, EVs face three barriers to adoption. There is a price concern, as you are paying a premium over buying a petrol car. There's still very few public charging stations. And finally, there is concern about the driving range, and while that concern has decreased, it is still an issue.”

In the case of nations like Norway and Iceland, where EV uptake is strong, the key partnership responsible for overcoming natural market inertia has been between government and consumers. A combination of strong, clear policy on one side and positive, progressive attitudes on the other has been central to the successful transition away from petrol and diesel in these nations.

“In the case of EVs, it's a chicken and egg problem,” Dr Vij says.

“Consumers are waiting for economies of scale to kick in so the prices can go down enough for infrastructure providers to enter the market so there are enough charging stations.

“But suppliers can't do that unless there is a market for it. That's where government needs to step in and either increase demand by offering consumer incentives, or incentivising suppliers to invest in charging infrastructure.

“In Norway, for instance, they have always had a very high tax on cars, because Norway in general is very committed to sustainability and zero net carbon emissions.

“This has allowed the government to provide strong incentives, such as removing the car tax if you're buying an EV, plus provide all sorts of other benefits like free parking in urban areas and free access to toll roads.

“In Australia, however, it is a different scenario between the government and the public. We have a strong fossil fuel lobby, and a government that has been very resistant to committing to net zero carbon emissions. We also have a strong petrol car culture, so attitudes are harder to shift.

“These factors make Australia very different to nations like Norway.”

Our wide brown land

Research fellow at UniSA Business Dr Ali Ardeshiri has expertise in human behaviour in connection with urban, transport and environment-related contexts. Like Dr Vij, Dr Ardeshiri sees the EV situation as a chicken and egg problem; and, he also emphasises the problem is different in Australia than in many nations with strong EV uptake.

“You need to look at the size of Australia versus some of these countries,” Dr Ardeshiri says.

“Australia is much larger, so the cost of infrastructure and the scale we need to implement that at in Australia is much higher than many other countries.

“The other challenge in Australia is that policies are mostly being developed at a state level, not a federal level, so New South Wales might decide to take one approach to providing incentives for EVs, but Queensland or Victoria might have different ideas.”

Even if we were to reach agreement on infrastructure across the nation, Dr Ardeshiri’s research suggests Australia faces another unique challenge in incentivising EV uptake.

“Imagine the government has $10,000 to use to subsidise the purchase of an electric vehicle,” he says.

“Should that $10,000 be given to the consumer in terms of a rebate or an incentive, or should that money be given to the manufacturer to bring down the production costs of EVs, reducing the purchase price?

“Our research shows that if a consumer sees a drop in the market price of the EV car by $10,000, they are much happier than if that $10,000 is given to them as a rebate or incentives in terms of electricity reduction.”

In other words, government investment in the EV industry is likely to be an effective way to improve EV uptake. The problem there, of course, is Australia no longer has any automotive industry to speak of, let alone an EV industry the government can partner with.

“We need to talk about what are we doing with our auto industry in Australia,” Dr Ardeshiri says.

“One of the key parts of EVs’ success in Europe is that they have EV companies based there. They're using their local product, supporting their local industry.

“It is likely that would be the same in Australia – if we had our own product, many Australians would spend their money on their own product rather than a foreign company, because they want to spend it in a way that comes back to the community.

“Then if that $10,000 was spent to subsidise an EV local industry, not only is it providing an incentive to buy the vehicle because the price is lower, but you’re also creating jobs and supporting the long-term viability of local innovation.”

Made in Australia, for Australia

The experiences of UniSA’s Motorsport Club suggest there is both the appetite and the opportunity for an EV industry in Australia. The UniSA Motorsport team has existed since 1999, providing students and staff with an opportunity to apply a range of skills to the development of competitive racing cars.

In 2019, the team made the shift from a petrol vehicle to an all-electric model – The MLK-19E – and their experiences in doing so reflect many of the challenges and potential benefits of a similar shift for Australian consumer vehicles.

Scott Evans was the president of UniSA Motorsport at the time of the electric shift, and he says the team found that industry partners, far from being put off by the switch, were very enthusiastic.

“One of the big challenges for projects like UniSA Motorsport is resources, both in people and in funding,” Evans says.

“I thought both of those challenges could be potentially alleviated by going electric because you bring in a lot more interest from a lot of different areas – the low carbon energy initiatives, the more advanced technologies, the more marketable outcomes.

“Taking that to industry for funding is easier to gain traction because you're saying, ‘Hey we're taking on this green form of motor sport and looking to the future.’ And that’s exactly what we found.”

Although Evans says attracting funding was still challenging, the results speak for themselves – the shift to an EV required a budget that was an order of magnitude larger than the budget the club had for their petrol vehicle, but nonetheless they achieved it.

“It made sense for our sponsors and supporters,” Evans says.

“Electric vehicle innovation is where job growth is, where all the new ideas are, where banks are willing to lend at low interest rates – ultimately, this is where big corporations are going to throw some big bet money to get a nose ahead of the game, rather than investing in those older technologies.”

Evans says the switch to electric also had a positive impact for the people working on the team. Hands-on experience working with an EV is experience that is vital to the future of automotive, but difficult to find in Australia.

As living proof of the value of that experience, Evans, who studied mechatronic engineering at UniSA, is now Project Manager at ZERO Automotive, an Adelaide firm that specialises in converting Toyota Landcruisers from diesel to electric for use in the mining industry.

“These vehicles are used underground and running diesel motors in enclosed spaces creates a very expensive set of problems,” Evans says.

“Ventilation for one light vehicle diesel motor may cost up to $100,000 a year. While our EVs cost more up-front, they don’t have those operation costs, so you actually make an appreciable saving over the lifetime of the vehicle.”

Evan says the success of ZERO Automotive – which is based on cost effectiveness and operational efficiency, not climate change considerations – shows a potential way forward for developing an EV industry in Australia.

“We're seeing some areas – and underground mining is a prime example – where EVs are actually the best option, and the big groups can see that now. They're like, ‘Hey if we can get this working, not only are we doing the right thing by our operators and using a green option, but it's actually the best thing for our bottom line as well.’

“That then starts to shift attitudes to EVs in other areas, and the industry can grow.”

Making the most of what we have

Current UniSA Motorsport president Hoang Pham says that while industry support for the team’s EV innovations remains strong, there are some notable gaps in local expertise. This, he suggests, is a key part of Australia’s current EV-apathy – and a very big opportunity.

“For instance, with the battery platform we built, we had to go all over the world to take a slice of their understanding and knowledge and then bring it together here and see what we can make out of it,” he says.

“This capability doesn't yet exist in Australia to any extent, and that meant we had to push the envelope to build the battery here.”

It may seem like a small problem – one battery for one university sports club car – but, echoing Dr Ardeshiri, Pham believes it’s small problems like this that add up to create the difficulty Australia is having adapting to an emission-free future.

“You often hear people say Australia is rich in all the minerals needed for making batteries, which is true – so why aren’t we making batteries?” Pham asks.

“Long story short, we’re not building batteries here because no one is using batteries here. Until we have a large manufacturer in Australia building a vehicle or something that uses batteries, the technology and the industry won't develop.

“And while that is frustrating from the EV perspective, it’s even more frustrating to think of the missed opportunities to add value to our mineral sector and develop world-class next-gen manufacturing.”

So, is the solution to Australia’s EV challenge as simple as ‘If you build it, they will come’? Perhaps, and it’s tempting to look at Tesla’s success to support that notion – in the company’s home state of California, the Model 3 and Model Y both boast the leading market share for their category.

Whether or not we could emulate that success in Australia, however, the real benefit of an Australian EV industry – the ‘big picture partnership’, if you like – may well be about much more than cars.

“When they put the ‘big battery’ in South Australia, some people were saying it would last three minutes and never pay itself off. But it paid itself off in an absurdly short period of time and has been the catalyst for those batteries to be established elsewhere in Australia,” Pham says.

“The battery modules that are in that big battery are the same modules Tesla puts in their cars and the same modules Tesla puts in every other one of their products. The same goes with an Australian EV battery – there's no reason we can't re-use it for other areas.

“But you've got to create the base capability in the country first and then you can begin talking about the transferable skills and technology, which could potentially define a whole new industry here in Australia.”

While many ideas have been suggested to improve uptake of EVs in Australia – from electric government fleets and public transport, to outlawing petrol vehicles – the most direct solution with the biggest impact could be a partnership between government, industry and researchers to kickstart a new era of Australian automotive innovation.

Yes, that would take a huge investment but, just as Australia is starting to reap wide-ranging benefits from re-joining the global space industry, we could also see big benefits from putting an Aussie-made electric vehicle on the road. After all, we’re all going to be driving EVs eventually anyway.

You can republish this article for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence, provided you follow our guidelines.