I started writing this blog on the 22nd Feb. I thought it'd be cool if I managed to post it at 22 minutes past ten pm. 22.22.22.2.22. The fact that you're only reading it now means I obviously didn't get it finished in time. I'm pretty sure that time is passing at an excessive speed at the moment and have made a note to consult the keepers of the atomic clock, just to see if they're over-winding it. I’m convinced that was 2021 a few minutes ago and now suddenly it is March... In the week that’s passed since 22.22.22.2.22 the world has shifted, again. We have welcomed our students joyously back onto our campuses and then watched in disbelief from afar as conflict erupted in Ukraine.

Tempus Fugit. Time flies.

The Latin version of which does sound particularly funny when you say it with my accent.

‘They say that time is the fire in which we burn’. Apparently. I’m not sure exactly who ‘they’ are, but it is an interestingly menacing line, and made more so when delivered by Malcolm McDowell just before he sets about his nefarious business which leads to the much-delayed demise of one James Tiberius Kirk. (Star Trek Reference Alert. (It’s tradition))

It’s actually a line taken from a poem by an early 20th Century American Poet, Delmore Schwartz, and the full context of it runs, Time is the school in which we learn, time is the fire in which we burn. The poem, Calmly We Walk Through This April's Day pertains to our human tendency to soldier on with the day to day, in spite of all we know. It reminds us to cherish the present as well. Much of the last couple of years could put one in mind of that tendency. In my personal glass-half-full cannon of psychology, I view it as central to a spirit of Enterprise, when all is said and done. It speaks to endeavour. But it can be tough going. A bit like undertaking a 12-month round of enterprise bargaining (compared to nine months in total for the last round) where so far only 1 of 40-something logged claims is approaching agreement in principle, even though the instrument being re-negotiated was deemed fully fit for purpose only two years ago, but now, somehow, suddenly isn’t, at least from one party’s point of view. I digress. We soldier on.

The reason I started writing this blog on the 22nd was also one of tradition. Traditionally, the Senior Staff annually go ‘on retreat’ and traditionally, shortly thereafter, I set about trying to myth bust the various rumours and misinformation that invariably percolates through the organisation as people speculate about what really went on behind closed doors. (I can hear Jon Blake in my head now.)

| Apparently, there were mysterious things in boxes; | True |

| They needed an epi-pen; | Not True |

| There was unusual personality profiling; | True |

| And ‘Trust Falls’; | Not True |

| And rats; | True-ish |

| And dope testing; | True-ish |

| And some of them failed the dope test; | Not True |

| And they put things up their noses; | Voluntarily |

| And the word ‘guardrails’ took on heightened currency; | True |

| And Andrew Pridham turned up and told people about his ‘no d*%kheads’ rule; | True |

So, there you go.

Some deep insight to the team and culture building that was undertaken across two days.

Frivolity aside, the retreat was all about one thing.

Trust.

If you’d like to ask anyone who was there what went on and we talked about, they’ll tell you, openly. We talked about how extended time under uncertainty, specifically the last few years and the challenges we have collectively faced, had diminished trust, had burnt it up. How ‘Schedule F’ (or Schedule F’d as I call it), the specific prudence measures that were implemented to manage our passage through Covid, had curtailed autonomy. And somehow strangely still are, even though they’re now in abeyance. They’re like a brake on empowered decision making. Even though we are back at pre-Covid approvals, processes and levels of authorities, things still feel curtailed. And when empowered autonomy is curtailed, whether perceived or real, people don’t feel properly trusted. Which goes right against the grain of our own core attributes – that a staff member in the University of South Australia ‘is trusted’. Little wonder we see it reflected in the culture survey results. We have lived our attributes so well, when an externality impacts on perception of one of them, the dissonance is writ large, across the organisation.

If you were unrealistically optimistic, you might say that we became victims of our own success. But that probably isn’t the case. External pressures required well-intended intervention that actively diminished the sense of trust. To protect employment levels. To keep the band together. To maintain business continuity. To provide the best possible learning experiences for our students in the safest practicable work environment for our staff. However, Trust is a two-way street. It flows in both directions. When people feel excluded from autonomous decision making, the first casualty is naturally going to be trust. ‘Why can’t I make that appointment?’ ‘Why can’t we cater the staff meeting?’ ‘Why can’t I enact our own working from home model at my local area level?’ ‘Why are my lectures online?’ ‘Where’s my N-95 mask?’ ‘Why do I have to wear a mask?’ ‘Why aren’t we mandating vaccination?’

Those last few questions simply serve to highlight that perspectives will always vary, just as perspectives on what ‘appropriate’ consultation is, or broad enough communication is, will always vary in the absence of any agreed definition. Consequently, a lot of effort, goodwill and patience gets needlessly burnt over time in the space between perspectives.

Fundamentally though, it’s been my experience that while people enjoy being in control of their own destiny, they also want certainty within guardrails and nobody really likes surprises. Unless it’s a X-lotto win. Then they’re fine with it. In the two-way street of trust perhaps an exhaustive list of every single step taken at every decision point should be published and updated on a daily basis. Probably not. It wouldn’t add much value and more importantly, it simply doesn’t speak to that two-way nature of trust. That’s the line, the tightrope, we’ve been trying to walk for several years now. Acting with the best interests of the institution, and our broad and large community at heart, while balancing the needs of the individual, and all the while hoping that common sense will prevail and that we can soldier on together for a while longer as one team as we get through these testing times together.

I sometimes must remind myself that while I’ve been here for nine years, espousing and living our one-team Enterprise approach – which, to my mind, is absolutely and deliberately positioned as a marked differentiator for UniSA, i.e., if you like the way we do it here, come and work or study here for those reasons, if you don’t like the way we do it here…. well, you can fill in the rest – but not everyone has been on all of that journey all of that time. The senior staff group left Pridham hall after the retreat with renewed connection, sense of purpose and energy. But only 9 of the group of 2022 senior staff group were in the senior staff group that set about crossing the horizon back in 2013. So we have to always cycle back, to check in on where we are against where we want to get to.

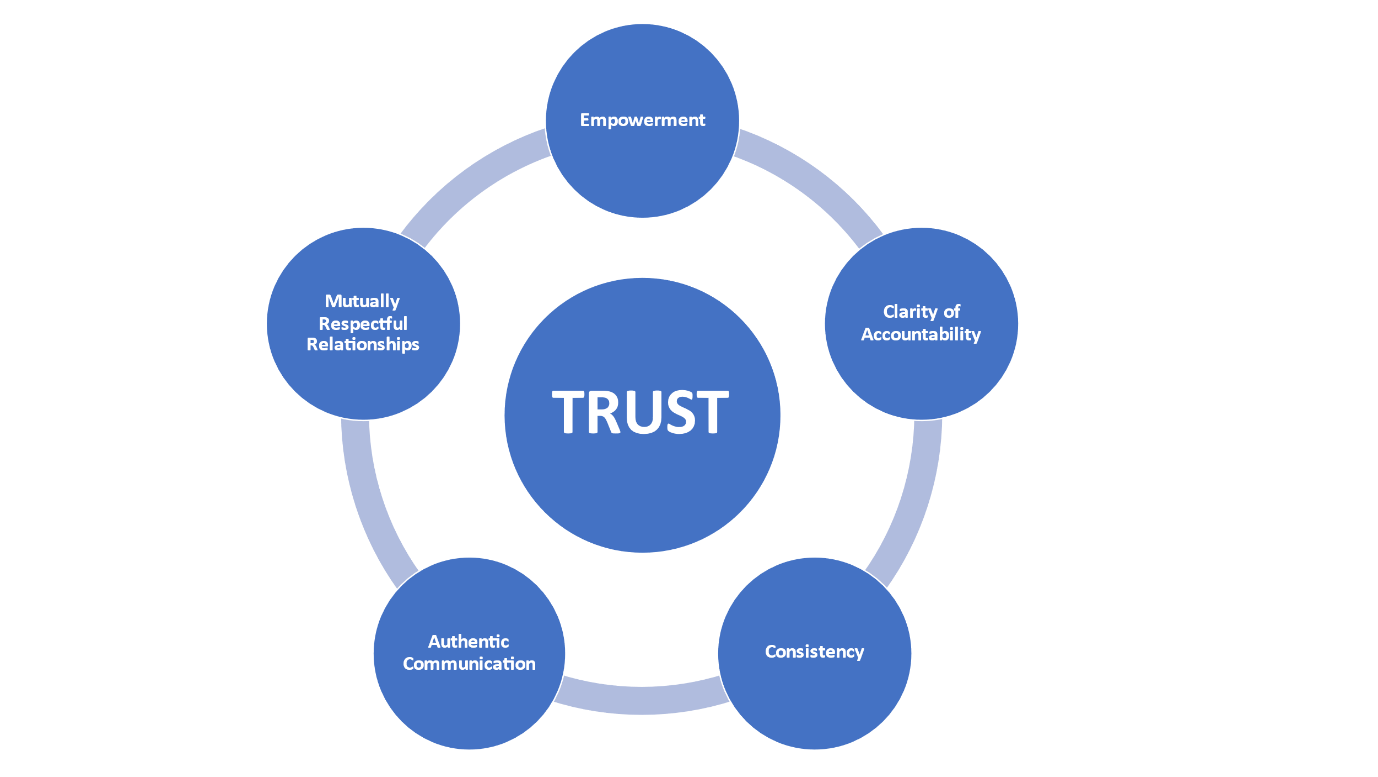

This simple diagram was one significant output from our discussion – and is intended to serve as a compass star for our navigation of post-Covid times as we crew this vessel together.

It’s not earth shattering work, but it is incredibly important. Just as our work to provide an enabling PDM framework or the development of a comprehensive remote and flexible working policy will be. These are two very specific, very important projects arising from the retreat that will now be co-created and enacted within our community. They’re intended as incremental continual improvements, with clear goals to be further sourced from within and across the organisation, recognising the wisdom of many heads and the value of many voices to broader input. Reflecting more of way we traditionally go about our business, over the way in which we have had to go about it of late, shifting us back to working for the university, rather than just in it.

Delmore Schwartz’s works later inspired music by The Velvet Underground and U2, which may or may not float your boat, but he is also known for something other than his poetry. The Delmore Effect is named for him. That’s a description of our human bias to avoid setting tangible or firm goals. It’s why we tend to say, “I want to get fitter”, rather than say, “I want to run a sub 28 minute five K in three months’ time”. The former is non-specific, non-threatening and fuzzy, and not as difficult to approach as the latter. It’s also much less likely to eventuate. We don’t have to hold ourselves as accountable when the Delmore effect is in play. But goals, specific goals, are important and we need to be wary of falling foul of the Delmore Effect. Without specific goals we could only settle for much less than the best and that is much less than UniSA deserves. The very nature of the shared goals of our University contribute to our success as much as our commitment to meeting them. Our shared level of trust in one another is something that should be reclaimed and be celebrated, because it has enabled us to achieve so much over time.

Tempus Fugit. Times change too. But the spirit of Enterprise remains the same.

Through The Big Picture, I hope that our whole community gains a greater and current appreciation of what is going on, how it fits together and how our activities connect and reinforce each other at a whole of enterprise level.

Archive

Tag cloud

- Across boundaries

- Alumni Awards

- Anniversary

- Antep

- Appointment

- Big challenges

- Big Ticket Items

- Birthday

- Budget

- Centre for Business Growth

- Chancellor

- Change

- Charles Bolden

- Communication

- Community

- Community International Borders

- Coordination

- Crossing the horizon

- Deadly Alumni

- Defence

- Dr Jane Goodall

- Education reform

- Engagement

- Enterprise

- Enterprise agreements

- Enterprise bargaining

- Enterprise Support Plans

- Enterprise25

- entrepreneurship

- Equity

- ERA

- Flexible learning

- Framework

- Funding

- Future Industries Institute

- Future University

- Global

- graduations

- Graduations

- Great Hall

- Integration

- Introduction

- ITEK

- Jeffrey Smart building

- Kemp Norton review

- Merger

- NASA

- Negotiation

- One team

- open day

- People

- Politics

- Practical Challenges

- Precincts

- Pridham Hall

- Programs

- Rankings

- Reconciliation

- Reconciliation plan

- Research

- SciCEd

- Sir Terry Pratchett

- Spirit of Enterprise

- Staff awards

- Strategic Partnerships

- Strategic Plan

- Tour Down Under

- Transformation

- Travel

- Unijam

- Vice chancellor

- Volunteer

- Watt Review

- Well being

- World Class