Consider the child who is born into entrenched poverty, into a household riven by family violence, parental mental illness and separation, unstable housing, foodinsecurity and sleep deprivation – lacking the nurturing that supports healthy development.

“Her or his prospects will be compromised,” Prof Segal says. “Our welfare safety net is in tatters and parents – often through their own devastating childhood trauma experiences – are struggling to offer the nurturing environment that all children need.”

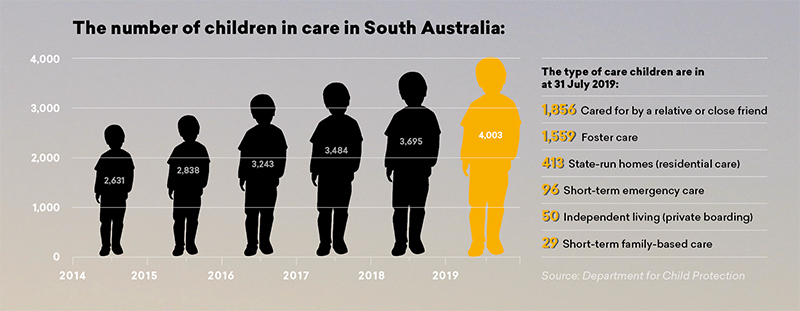

In 2017-18, nearly 15,000 children came to the attention of the Department for Child Protection in South Australia, with 4150 children in care and $504 million spent on child protection services.

Family violence, child abuse and neglect are sad facts of Australian life, borne out by distressing statistics which show that by the age of 10, one in five children has experienced harsh parenting, poverty, family separation, bullying, or been exposed to substance abuse and domestic violence.

"In order to cope with the unmanageable distress and fear, these children will often self-medicate with drugs and alcohol, potentially leading them down the path of crime.

"This shouldn't come as a surprise, but as a society we are quick to blame the perpetrator, when instead we should be taking collective responsibility to address the causes," Prof Segal says.

Her work is devoted to identifying the pathways into child maltreatment and the most cost-effective way to help children at risk.

She points to a “mammoth failure” to treat mental distress in infants, children, teenagers and their families, which too often morphs into adult mental illness and domestic violence.

Multiple studies, including by Harvard University's departments of psychology and psychiatry and Yale University’s School of Medicine, have shown that abuse or neglect of children causes their brains to grow differently. Toxic stress in infancy and early childhood changes the way the brain develops.

"Trauma – especially child abuse and neglect – is a primary pathway into violence. The evidence is overwhelming. While cultural mores can have some influence, it is telling that prison populations are full of men and women with histories of child maltreatment, major mental illness, drug and alcohol addictions, intellectual disability and brain damage. Maltreated boys too often turn into violent men."

Prof Segal says only by taking a long-term approach and allocating more money into proven parenting programs and family support services will governments make progress.

A NSW Government two-year trial of ‘treatment foster care’ for the most vulnerable children, offering carers intensive training, 24/7 support and up $75,000 a year to care for children, aiming for safe family reunification, is a promising step. The SA Government is considering a similar trial.

"Child abuse and the subsequent social, health and economic problems are preventable, but society needs to understand the causal pathways and ensure adequate family support is available," Prof Segal says.

"Every single family in crisis should have access to a highly skilled interdisciplinary team of social workers, mental health clinicians and other core services. Maternity services and early childhood centres also have a role in identifying and supporting those at risk."

A more controversial mind shift needs to happen in relation to “man-blaming”, she argues.

"Family violence is shocking, but the question is how should we respond? Some domestic violence websites adopt a radical feminist view of family violence as the result of disrespect by males of females, an old-fashioned male stereotype. This dominant dialogue demonises men, doing nothing to address fundamental causes of violence.

"A healthy society rests on functioning families. Children will thrive better in a nurturing and supportive environment, ideally with access to two loving parents. In shaming men and not encouraging them to access the services and counselling they desperately need, we are losing the opportunity for healing and repairing relationships and families.

"Damaged brains can be rewired and repaired with compassion, not through a punitive, shaming and angry response directed at men. Yet, this is what we are doing in Australia."

To this end, Prof Segal is calling for more to be done to encourage significantly more men into early childcare and social work – traditionally female-dominated areas.

"We need to put the same energy into encouraging men to pursue careers in social work, early childhood, nursing and primary teaching as we do into encouraging women into STEM. That would make a huge difference to the health of our families."

Deputy Director of the Australian Centre for Child Protection (ACCP) at UniSA, Associate Professor Tim Moore, is a strong advocate of positive male role models for troubled youth but says they need to be more than mentors.

"Sometimes male youth workers can almost reinforce or excuse problematic behaviours in men, so it’s important they challenge those behaviours," Assoc Prof Moore says.

"I also think that we need to change the perception that the caring professions are women’s work. A lot of men feel more comfortable talking to other men about issues relating to masculinity because that is often at the core of their behavioural issues."

A recent ACCP project looking at family violence found a history of fractured relationships over multiple generations.

"Overwhelmingly, people talked about their own experience of family violence during their childhoods, with many of the fathers not having positive male role models in their youth,” Assoc Prof Moore says. “They felt ill-equipped to be good dads themselves.

"Many of the parents didn’t know what a good relationship looked like and had no idea of how to manage conflict in a healthy way. They only knew violence and thought that was normal.”

Assoc Prof Moore says early intervention is the key, teaching girls from an early age to expect more from their relationships and showing boys how to relate to women in a positive and respectful way.

The other mindset that is proving difficult to shift among boys and men is that reaching out to others for support is a sign of weakness. As a result, male suicides and self-harm attempts are still unacceptably high.

"I think these days men are being confronted on so many more levels, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing – take the #MeToo movement for example – but we need to ensure they are getting as much support as possible to embrace change."

FIND OUT MORE | Australian Centre for Child Protection

The MENtor Program for Males in Early Childhood Education

Early childhood teacher and UniSA graduate Rob Lister pictured with some of the children at Gowrie SA’s Underdale centre, where he works. Photo by Cath Leo

Early childhood teacher and UniSA graduate Rob Lister pictured with some of the children at Gowrie SA’s Underdale centre, where he works. Photo by Cath Leo

Male teachers caught in the headlights

"We are taught to be scared of adults and adult men are taught to be scared of kids."

This comment from a schoolboy highlights the dilemma facing male educators today – the fear of overstepping the line at the expense of a child’s need for human love and comfort.

Case in point: a lost child cries in a shopping centre. Men look around desperately for a female to step in, hug the child and reassure them that mum or dad will soon be found.

Does this make the child feel safer, knowing that men are fearful of playing the role of comforter? Commonsense says no.

"According to UniSA lecturer in Early Childhood Education Dr Martyn Mills-Bayne, this is the reality that male teachers live with every day.

"On the one hand, parents should be reassured that all teachers – male and female – are now subjected to the most stringent checks in history,” he says. "It also means that men are constantly afraid of how they will be perceived when working with children."

The scrutiny is one reason why men comprise only two per cent of the global early childhood workforce. The risks of rumours and accusations are always present, and careers can be ruined without due cause.

Other factors discouraging men from working in the sector include perceptions and pay.

"Society still views early childhood teaching as a woman’s domain, even though men are parents too, and just as invested in their child's development and education," Dr Mills-Bayne says.

The low wages for early childhood educators also make it a less favourable career choice. A significant proportion of those who do work in the field end up in managerial or leadership roles, moving away from the day-to-day interaction with young children.

Male students enrolled in UniSA’s early childhood degrees make up 4 per cent of the student cohort – double the national average but the attrition rate is still high due to the isolation that many men experience.

That's one of the reasons why Dr Mills-Bayne established the MENtor Program for Males in Early Childhood Education in 2011 to support male early childhood education students at UniSA. The program has broadened beyond UniSA’s Magill campus and helped drive the establishment of a national body – the Australian Association for Men in Early Childhood – in 2018.

Dr Mills-Bayne says men working in early childcare education can have a profound impact, particularly for children who have no father at home, or lack a positive male role model.

"In situations where children are surrounded by aggressive or emotionally distant men at home, skilled male teachers can teach young boys that it’s okay to show their emotions,” he says. “The earlier we can start working with boys to develop empathy, the greater our chances are of avoiding another generation of men who struggle with their emotions."

Australia could also learn from the example of Norway, which has set an ambitious target of 20 per cent of male early childcare workers. UniSA Early Childhood Education graduate Rob Lister is one of three men working as early childhood educators at Gowrie SA, which offers childcare and kindergarten programs at Thebarton and Underdale.

In his experience, fathers are more willing to interact with childcare centres which have a mix of male and female staff.

"Having males working in early childcare creates a more inclusive space for families,” Lister says. “Parents can connect with and talk about their child to both male and female childcare workers and fathers have someone they can relate to.

"It's also important to be a positive role model for families that have experienced trauma or hold stereotypical images of males. By working in this sector, I can demonstrate that men can be nurturing, caring and playful."

When it comes to addressing the low proportion of men in early childcare, Lister echoes the sentiments of many women in political life. “We don’t want to rely purely on incentives and quotas; we want quality male early childcare educators," Lister says.

"This line of work is extremely rewarding and definitely worth pursuing. The relationships that we create and the educational programs we are involved in delivering make it a very satisfying career for men."