In a year of political shocks - Brexit and the election of Donald Trump in the US - 2016 saw the mainstream media and - in a vast frenzy across Twitter and Facebook - social media awash with discussions about fake news.

The idea that this is the first time in history where objective facts hold less influence on public opinion than rational minds believe they should, is in itself a fiction. Handling the truth lightly has been stock and trade for politicians, propagandists and business leaders for a very long time.

If anyone has an interest in ensuring that researchers remain a trusted part of the community, it is Dr Susannah Eliott, CEO of Australia’s leading repository for science communicators, the Australian Science Media Centre, and she says experts need to be concerned about this latest global “disruption”.

“Scientists and other academic experts tend to believe that if you keep throwing facts at people they will eventually just get it,” Dr Eliott says.

“But times have changed and on the widest scale, public trust has been eroded.

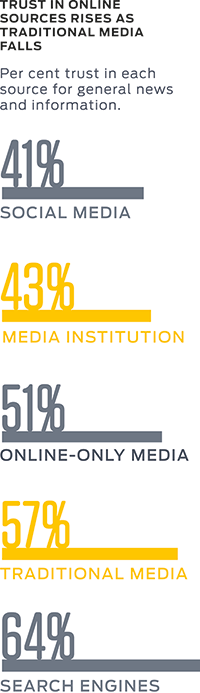

The 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer shows public trust in media fell to an all-time low in 17 countries and trust in institutions of government, CEOs, business and NGOs to do the right thing, also dropped. Equally troubling, the barometer shows that independent experts and academics are regarded as no more reliable for facts as another person who is “just like you” and search engines are now regarded as a more credible source than anything that has been “edited by humans”.

Dr Eliott cites a recent study from Stanford University as further evidence that fake news is gaining purchase. The researchers tested almost 8000 students from middle school through to college age to see how well they could tell the difference between fake and true articles and stories on social media. The results, released in November 2016, were alarming.

“Despite young people being tech-savvy they don’t seem to have the assessment skills to tell the difference between what is real and what isn’t,” she says. “They found four out of 10 high school students believed stories based on a headline and photo alone.

“It shows we can do a lot more to teach people how science works, how researchers establish findings and how to be more questioning of sources.

“And researchers need to put much more effort into their communications.

FALSE INFORMATION SPREADS FASTER THAN EVER

“Because of the internet and social media, the mechanisms for channelling propaganda and unsubstantiated ideas have never been faster or broader,” she says.

“Because of the internet and social media, the mechanisms for channelling propaganda and unsubstantiated ideas have never been faster or broader,” she says.

“To resist these trends, researchers need to know how to manage their personal credibility and how to communicate in ways that include rather than exclude listeners and readers.

“They need to be engaged and aware – they need to understand the societal context for their work – an anchor point where everyday people can connect with the research.

“It’s important to think about who you are talking to – doing an interview for Triple J is quite different than one you might do for Lateline – and you need to frame your communications accordingly.”

She says while it is vital that researchers engage with the media and comment on proposed policy initiatives, they should avoid becoming political.

“As soon as people believe a researcher has an axe to grind, credibility plummets,” Dr Elliot says.

“None of this is easy. These are real skills that researchers need to develop and they require thought and preparation.”

Dr Eliott says many researchers focused intently on their work, fail to understand the importance of excellent communications skills.

“Researchers can’t afford to be lazy or arrogant; if anything will support experts’ credibility, it will be engaged, relevant, unbiased communications about quality research.”

UniSA senior lecturer in Public Relations Dr Collette Snowden says that in an environment where the tradition of evidence-based reasoning has been undermined, it is essential to revitalise journalism and communication through education.

“The belief that people will follow a logical path using deductive reasoning has gone out the window,” Dr Snowden says.

THE POWER OF EMOTION OVER LOGIC

“Increasingly we find people are more likely to start with a view and simply find content to support that view. The internet and social media amplify that practice by allowing people to narrow their search for information to fit their opinions. The power of emotion over logic is actually very strong.”

She says the response has to be to raise journalistic standards.

“We are up against some powerful challenges,” Dr Snowden says. “It is important to consider how people get their news and what that is doing to the way they process information. If we look back to theorists like Marshall McLuhan, who predicted an internet future well before its invention, we can see that the medium does indeed influence the message.

“Through complex algorithms, social media delivers targeted information based on personal preferences. Add to that the shareability that is a feature of social media platforms and we see that the medium is as important to news engagement as the content because it is being received in environments that feel personal and trusted.

“But as most people restrict their consumption to a few favourite sites and share content with people they already know, communication becomes narrower.

“While fake news is by no means a new phenomenon - propaganda is a mainstay of political positioning - today the capacity to disseminate false news at breakneck speed is unprecedented.”

She says journalists need to be better prepared to separate fact from fiction, and identify disinformation, whether they are covering politics, science or finance.

“Never has there been more academic research available to help them, and never has it been more accessible, but filtering that information needs to be done with rigour.

“We must instil a discipline of questioning everything – source checking is vital.

“We also need to give more attention to teaching journalism and communication students the importance of impartiality. This is evidence-based practice.”

Dr Snowden says the concept of journalists as an elite group acting with self-interest, a notion promoted repeatedly by the Trump campaign and frequently alluded to in Australian politics, needs to be challenged. But the media industry must also play its part, and so far, she says, there is not a lot of evidence that it will.

“We really need to unpack the murky connections between media, showbiz and politics and remove the motivation for celebrity journalism, get rid of indulgent bylines and discourage reporters from personal brand-building.

“Ultimately what we do as educators in the face of truth disruption is make a commitment to discuss it in classes, analyse what’s happening and reinforce that the best journalists have often been anonymous, dedicated to speaking truth to power and capable of putting aside big egos for the greater good.

“Ultimately, great journalists need to be able to stand apart from the pack, and report the facts.”

DISRUPTED SOCIETIES

UniSA sociologist Professor Anthony Elliott says our yearning for certitude is reflected in the rise and popularity of leaders like Trump and movements such as Brexit.

“People have been unprepared for both the size and speed of change,” Prof Elliot says.

“Unlike earlier industrial revolutions, this one is turbo-charged. Faced with that kind of change, one predictable human reaction is to want to slow things down and focus narrowly.

“While we may not be at the ‘end of history’ as political scientist Francis Fukuyama once described, we seem to be at the outer edge of history and into experimental territory.

“So many of the professions and industries are being outstripped by change so rapidly that it is hard to keep up.

“There is great disruption in key professions – journalism, medicine, management, economics – where the outlook is that there will be less and less need for a professional elite as they are replaced by robots and para-professionals.

“This is acting to level out our notions of expertise.

“Where professionals – the doctors, accountants, scientists and reporters - were once the gatekeepers of truth and the source of facts – now people are drowning in information.”

Prof Elliott says responses to that uncertainty split two ways.

“Either you practice the art of doubt, which is an uncomfortable space to live in all the time, or you seek out the equanimity of certainty,” he says.

"Political messages that emphasise getting back to the past when things were simpler, better and less fractured, are therefore emotionally appealing – no matter how unrealistic or unfounded they are.”

This desire to bring back familiar order is heralding a new phase, something Prof Elliott says is an attempt to decouple from the reality of frenetic technological progress.

“Everywhere we are seeing signs of de-globalisation and the undermining of trust,” he says.

“But the story unfolds - this is our ‘post-truth’ disrupted reality for now. There is more change ahead.”

Political Photos L-R: JStone, Ms Jane Campbell, Twocoms, Ms Jane Campbell, eddtoro / Shutterstock.com