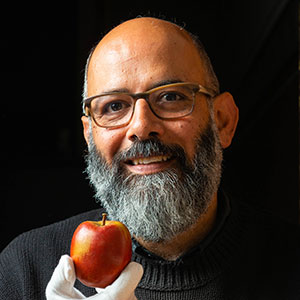

Meet Tony Kanellos.

As manager of Cultural Collections at the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium and curator of the Santos Museum of Economic Botany, Kanellos is custodian to a treasure trove of objects that connect us to the botanical world. Carefully curated and displayed, the collection offers important lessons about life, culture and the essential roles that plants play in human existence.

“This collection is brimming with stories about life,” says Kanellos, a UniSA graduate.

“Not just South Australian stories, but stories of all cultures - and many of the cultures that now make up South Australia.

“When you walk around this museum, you see the commonality of all cultures – we all need food, fibre, and medicine, we all need different ways to express ourselves.

“But at the heart of it, culture is humanity, and while we celebrate different cultures, all people are the same and we’ve all depended on plants since day one.”

The museum was established in 1881 to teach early colonists about the different uses of plants – for food, fibre, medicines, dyes, tools, shelter, even musical instruments. As the only museum of its type to survive in the world, it’s a repository of stories and curiosities, from the origins of gin and tonic rooted in anti-malarial drugs dispensed to British soldiers, to the seafarer’s illusion of a diving mermaid conjured by the shape of the world’s largest seed, the coco de mer, floating in the ocean (see right).

Yet behind the curiosities – and the beautiful 19th century feel of the museum – is a story as important now as it was then: sustainability and biodiversity.

“Walking into the museum is like stepping back in time,” Kanellos says.

“But keeping the original look and feel of the museum was intentional because we wanted to remind people how fundamental plants are to our existence and that we must appreciate and value their significance if we want to ensure our way of life.

“Of course, people didn’t use these words [sustainability and biodiversity] back then, but the concepts today remain the same.”

Culture is about the lives of everyday people

Connecting past, present and future is a common mission for all of the State’s cultural institutions. For cultural expert and scholar, UniSA’s Professor Susan Luckman, the sharing of stories, histories and narratives is an illustration of how people make sense of the world.

“When people think of ‘culture’ they often relate this to high-end experiences, but of course culture is really just the everyday practices of people getting on with their own lives: it’s the tattoos, it’s going to the footy on the weekend, it’s everything we do that makes us human,” Prof Luckman says.

“For centuries we’ve been challenging understandings of culture as the official record. We need to ensure our collections are diverse and representative of both the past and the present, because this will become tomorrow’s history.

“Increasingly, cultural institutions are doing wonderful work in this space to make sure their collections capture everybody’s stories, not just those who get to write history.”

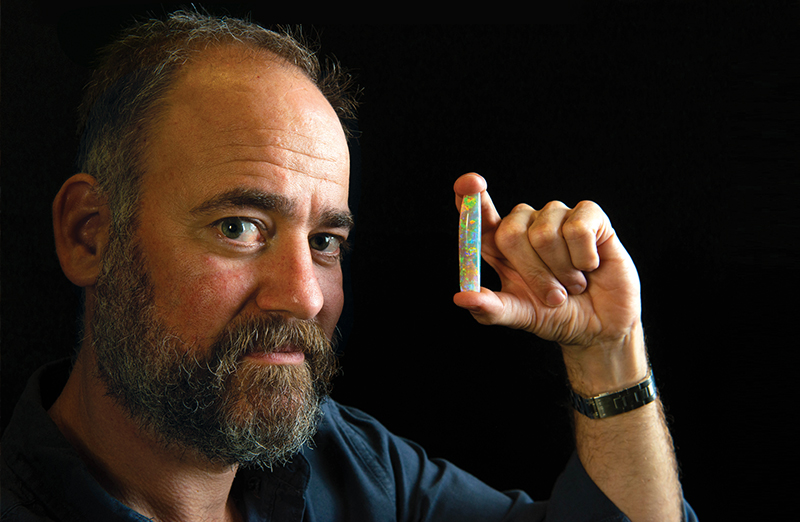

Enter Mark Gilbert, a librarian working with South Australiana, rare books and special collections with State Library of South Australia. The UniSA Library Studies graduate is a curator and custodian of culture. Part of his role is to ensure the library collects a broad range of items that represent South Australia.

“The library exists to look after the State’s heritage,” Gilbert says. “This encompasses everything from 1000-year-old manuscripts to SA’s first newspaper, and even today’s latest pizza menu.

“In that sense, the library’s boundary doesn’t stop. We collect anything and everything that is published in SA with the intent that we’re capturing what’s important and meaning-ful to South Australians now and in the future.”

The breadth and depth of the library’s collection spans more than 60 kilometres of shelving, and with the collection ever-expanding, it’s not surprising that storage is an ongoing challenge.

“Increasingly, we’re digitising records to make sure the collections, and the stories within them, last and that people can more easily access that information,” Gilbert says.

“One of the most emotive collections we’ve digitised is that of the South Australian Red Cross Information Bureau, which holds enquiries from family and friends about missing Australian soldiers in World War I.

“Until 2013, these were only accessible on the bureau’s complicated and onerous card index. Now that this is online, more people can access answers about their loved ones from WWI.”

Despite the potential that digitisation has, Gilbert says that it’s unlikely that everything will go online. It’s a challenge Associate Professor Christine Garnaut, director of UniSA’s Architecture Museum, understands well.

As caretaker of a one-of-a-kind repository of South Australian architectural records, Assoc Prof Garnaut is leading a national research project to develop a framework for archiving ‘born digital’ architectural records. She says maintaining digitally created items is an ongoing issue.

“For the past 30 years or so, architects have been creating building designs with CAD – computer-aided design, but as programs become redundant, we can no longer read the files,” Assoc Prof Garnaut says.

“So, we’re investigating ways to preserve digital records, so they last beyond the technology through which they were created.”

With a collection of more than 200,000 items comprising everything from beautifully hand-drawn blueprints to an architect’s travel journal, Assoc Prof Garnaut says each item forms an important part of South Australia’s heritage.

“The story and context bring a building to life,” Assoc Prof Garnaut says. “These are not just technical records, they are the cultural and social history of South Australia, written in a visual way.

“The records share the biography of a building: sometimes a building has a long life, so the records provide important insights into the way people lived and worked. But at other times, a building has a short life – shorter even than that of the architect – which makes the records the only remaining traces of the building.

“Architectural records help us understand our place, our history, why something existed, its purpose and its evolution to the present day. It’s vital these are protected.”

Does technology protect or compromise art?

The rate of obsolescence is also felt strongly in the field of conservation. Rosie Heysen, paintings and frames conservator with Artlab Australia, the largest conservation centre in the Southern Hemisphere, says authenticity is an issue, especially for time-based media.

“When an artwork is created on an old medium such as VHS, we question whether it should always be displayed that way because the medium is so intrinsic to the art itself,” the UniSA Cultural Management graduate says.

“But the challenge is, when VHS is no longer available, what can it be played on? Should we transfer it to an alternate format, comparable with contemporary media equipment? Does this go against the artist’s intention? These are all questions that arise, and they can present significant ethical issues.

“Recently, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam exhibited 3D printed copies of Van Gogh’s most famous works. This received mixed reviews … mostly because the art wasn’t the ‘real thing’, it wasn’t authentic.

“In other ways, 3D printing can present new opportunities for conservation, from recreating lost elements of artworks, to enabling hands-on interactive activities.”

Prof Luckman says that experimentation with 3D printing is an exciting development for museums.

“People can’t touch old artefacts but if they were replicas, they could,” Prof Luckman says.

“Providing tactile experiences can help people better engage with objects, to get a real understanding and appreciation for them.

“As a society, we need to ensure our cultural collections are as accessible as possible – to both a wide range of people and a wide range of ages – so that as a community, we have the opportunity to learn, engage and reflect on all the things that make us human.”

Sometimes, preserving culture is about collecting stories to retain understanding. Through UniSA’s Weaving the Murray project, researchers and artists travelled the Murray

River collecting artefacts and narratives to culturally map the river’s role in Australia’s development.

Lead researcher, Professor Kay Lawrence, says one of the most rewarding parts of the project was connecting with Ngarrindjeri weavers to explore issues of identity, community and loss in the present.

“Bringing together both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, the Weaving the Murray project proved a powerful tool for rethinking the past and exploring issues of identity and community,” Prof Lawrence says.

“As two very different cultures intercepted, we talked and shared our different histories but also our commonalities through shared concerns for the future of the Murray River.”

Museum collections can help rewrite history

Preserving and displaying lost arts, species and rare artefacts is the role of the South Australian Museum. Manager of exhibitions and special projects, Tim Gilchrist, says historic objects can also revive culture.

“Abe Muriata is Australia’s leading expert of an Indigenous woven basket called a jawun,” Gilchrist says.

“His grandmother taught him how to make them when he was a boy, but the craft was lost over time. Today, by studying collections in museums, he was able to relearn the craft of his ancestors and make it a contemporary practice again.”

But culture is not the only revival occurring at the SA Museum. As the UniSA graduate says, new research on old treasures can also reveal exciting findings.

“We have a project under way that’s testing hair samples of Aboriginal people from the late 1930s.

“Of course, all the permissions (current or ancestral) have been collected, but by analysing the samples, it’s possible to determine the early distribution of Aboriginal people across Australia.

“It’s retelling the story of Aboriginal populations and could rewrite history. But what it shows is how the collection can hold secrets that are yet to unfold.”

While lifelong learning is central to the work of SA’s cultural institutions, accessibility and relevance remains top of mind. Lisa Slade, assistant director for artistic programs at the Art Gallery of South Australia, says creating a sense of curiosity is essential for maintaining an interested audience.

“Good art is transformative,” Slade says. “Our job is to collect it, seek it out, commission it, and bring it to life through audience engagement.

“This comes through thinking about exhibitions differently, placing things within conversations, rather than within a timeline, which is the more traditional way of showing art.

“We’re constantly reviving the collection’s icons – the Tom Roberts, the Heysens – to find new narratives and new possibilities, to inspire and attract audiences.

“In some ways, cultural institutions are the temples of the 21st century: places of congregation, solitude and reflection. Places where you can almost step out of your life – just for a moment – to contemplate and consider the past, present and future.

“It’s a journey, and we simply provide the path.”